The Promise vs. The Track Record

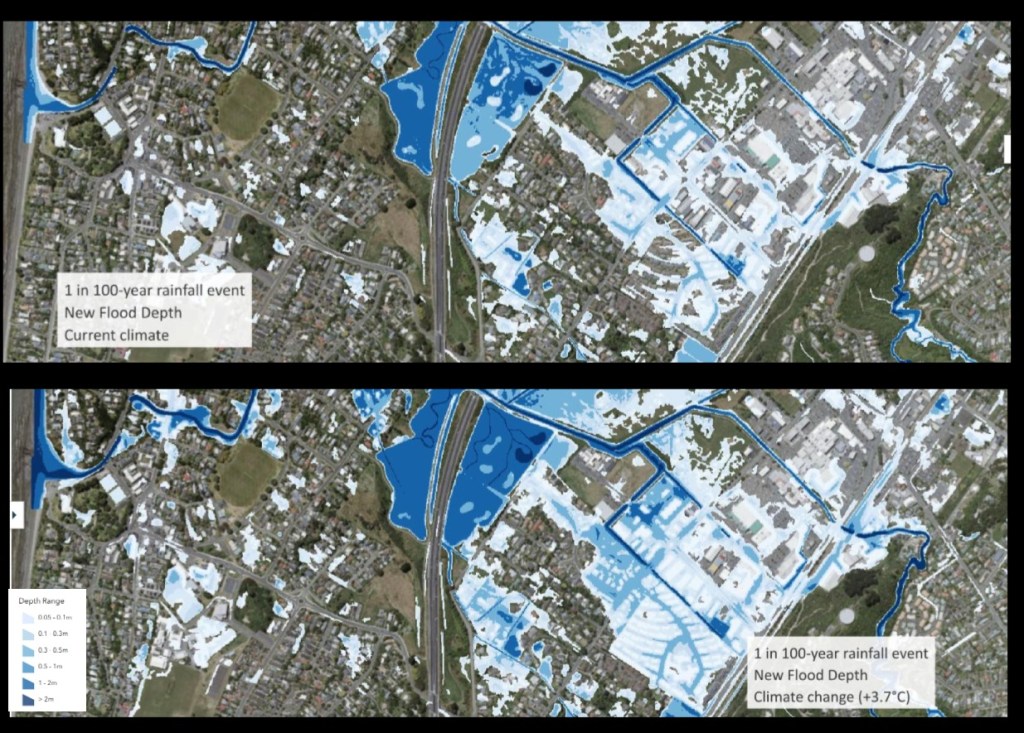

Kapiti Coast District Council is asking ratepayers to trust their latest flood modelling exercise – a sophisticated computer simulation using “advanced modelling techniques” and climate projections stretching to +3.7°C of warming. The maps look impressive, the technology sounds cutting-edge, and the scientific methodology appears robust. But there’s a fundamental question that deserves an honest answer: why should ratepayers believe these models when virtually every previous generation of flood modelling has proven inaccurate?

The Cost of Being Wrong

While KCDC presents their flood mapping as a planning tool, the real-world consequences for ratepayers are immediate and severe:

Insurance Premiums: Risk-based pricing means properties newly identified as “flood-prone” could see insurance costs double or triple overnight. Some may become uninsurable entirely, as insurers refuse coverage for highest-risk categories.

Property Values: Homes incorrectly flagged as high-risk will lose value immediately. For many ratepayers, their home represents their largest asset and retirement security.

Rates and Infrastructure: Council will use these maps to justify expensive stormwater upgrades and infrastructure projects. Ratepayers will fund these through rates increases, regardless of whether the flood risk is real or imaginary.

Development Restrictions: New building restrictions based on flawed modelling could artificially constrain housing supply and economic development for decades.

The Modelling Industry’s Credibility Problem

Research into flood model accuracy reveals disturbing patterns:

- Data Quality Issues: Flood models suffer from “incompleteness, inconsistency, and accuracy deficits” in their underlying data

- Elevation Errors: Basic elevation data can be wrong by over 5 meters – enough to completely invalidate flood predictions

- The Precision Trap: High-resolution maps create “false perception of intrinsic skill” – they look authoritative but may be completely wrong

- Fundamental Limitations: As modelling experts note, “a flood model is only as good as its weakest component”

Most concerning is the industry’s own admission that models are often wrong, but this uncertainty “is often ignored in the rush to present ‘precise’ predictions to end users.”

Climate Modelling’s Extreme Scenarios

KCDC’s use of +3.7°C warming scenarios raises questions about proportionality. While these extreme projections may be scientifically plausible, they’re being used to make immediate decisions affecting ratepayers today. If a 1-in-100-year flood under extreme warming becomes the basis for current insurance pricing and development controls, ratepayers bear the cost of hedging against scenarios that may never materialize.

The Accountability Gap

Perhaps most troubling is the complete absence of accountability when models prove wrong. Unlike weather forecasters, flood modelers face no consequences for inaccurate predictions. When maps incorrectly identify areas as flood-prone:

- Insurance companies don’t refund overcharged premiums

- Property owners receive no compensation for lost value

- Council doesn’t reimburse ratepayers for unnecessary infrastructure spending

- The modelling companies simply release “updated” versions

The costs are socialized through higher rates and insurance premiums, while the profits from modelling contracts remain private.

A More Honest Approach

Ratepayers deserve transparency about model uncertainty rather than false precision. KCDC should:

Acknowledge Limitations: Explicitly state the error margins and confidence levels in their modelling, rather than presenting maps as definitive truth.

Provide Recourse: Establish mechanisms for ratepayers to challenge incorrect classifications and seek compensation when models prove wrong.

Phase Implementation: Avoid immediate regulatory changes based on unproven models. Use a graduated approach that allows validation against real-world events.

Independent Review: Subject modelling assumptions and methodologies to independent peer review by experts not connected to the modelling industry.

The Bottom Line

Kapiti Coast ratepayers are being asked to accept significant financial costs based on computer models with a poor track record of accuracy. The sophisticated technology and climate science credentials don’t change the fundamental reality: these models may be wrong, and ratepayers will pay the price.

Before implementing far-reaching changes to insurance pricing, development controls, and infrastructure spending, KCDC owes ratepayers an honest conversation about model uncertainty and the real possibility that their expensive new flood maps may prove as inaccurate as their predecessors.

The question isn’t whether flood risk exists – it clearly does. The question is whether we can trust computer models to accurately quantify that risk well enough to justify the massive financial impacts on ordinary ratepayers. Based on the evidence, a healthy dose of scepticism seems entirely warranted.

Leave a comment